A New Look at Iran’s Complicated Relationship with the Taliban

Eight years ago, I took part in a meeting among people from several different countries — Iran, various European countries, Afghanistan, Turkey, and the United States. I was a part-time consultant to the U.S. government at the time, and most of the group had been or — at least — were close to government officials. These are known as “track-two meetings.” During one of the sessions, a European participant charged Iran with supplying military aid to the Taliban. A retired Iranian diplomat responded indignantly. “How could Iran supply aid to its sworn enemies?” he asked. I responded that Iranians were not such simple-minded people that they could have only one enemy or one policy at a time.

Iran’s position on the agreement between the United States and the Afghan Taliban signed in Qatar earlier this year may likewise appear confusing. In 1998, Iran nearly went to war with Afghanistan, then mostly under Taliban rule, when Pakistani fighters allied with the Taliban killed 11 Iranian civilians in Mazar-i Sharif, including nine diplomats. In 2001, Iran helped the United States remove and replace Taliban rule in Afghanistan with both military and intelligence support on the ground in Afghanistan and diplomatic support at the U.N. talks on Afghanistan in Bonn. For years, Iran opposed political outreach to the Taliban and rejected any distinction between them and al-Qaeda. As the U.S. military presence in Afghanistan approached its 20th anniversary and the United States withdrew from the nuclear agreement with the Islamic Republic and imposed additional sanctions, Iran echoed the Taliban in calling for the complete withdrawal of U.S. military forces from Afghanistan, the main Taliban demand that the United States met in the Doha agreement. Iran also began supplying Taliban commanders in western Afghanistan with weapons both to send a message to the United States and to deal with threats on or close to the Afghan-Iranian border. Yet Iran has also been the most outspoken country in the world in denouncing the agreement, claiming that it amounted to recognition by the United States of the Taliban’s “Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,” which Tehran says constitutes a threat to the national security of Iran. Iranian officials who welcomed Taliban Deputy Leader Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar to Tehran, something Donald Trump could only dream of doing at Camp David, claim they told the Taliban that the re-establishment of the Emirate would cross a red line for Iran. Russia, which has taken the same position on the Emirate, has nonetheless endorsed the agreement as the best way to achieve its top goal in Afghanistan: ousting U.S. military forces from their bases on the former southern border of the Soviet Union. According to an Iranian official who requested anonymity to speak with me freely, Russian officials have asked their Iranian counterparts if they really want the United States to withdraw from Afghanistan or not.

Ralph Waldo Emerson famously wrote that “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines.” For Iranians, there is nothing “little” about Iran, its statesmen, philosophers, and divines, as they are heirs to thousands of years of unbroken history and civilization. Though Iran’s policy toward Afghanistan may lack a foolish consistency, it has placed Iran in what may be its best attainable position in Afghanistan: No one trusts it, but no one wants to antagonize it either.

Iran’s view of the Taliban has largely been derivative of its analysis of the relationship of the Taliban to the top threat to the Iranian state, the United States. In this respect, Iranian policy toward the Taliban resembles U.S. Cold War policies that evaluated groups in other countries as a function of their relationship to the Soviet Union.

Iran was involved in the establishment of the “Northern Alliance” (Ittilaf-i Shamali) that overthrew Afghan President Mohammad Najibullah in 1992, and constituents of that alliance predominated in President Burhanuddin Rabbani’s Islamic State. Iran had excellent relations with Ismail Khan in Herat and with Ahmad Shah Massoud in the northeast. Until 1996, it used northern Afghanistan as a staging ground for aid to the Islamic movement in Tajikistan.

While Rabbani was a Sunni of the Hanafi school, the fact that he was Persian speaking was a source of solidarity. The opposition to Rabbani’s government led by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, with the support of Arab Islamist volunteers and with backing from Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, looked to Iran like another case of Wahabi “mullahs made in Britain” or the United States to oppose Iran. Iranian leaders at that time openly spoke of the Taliban as being supported by the United States. Such suspicions are resurfacing today as a result of the U.S.-Taliban deal in Doha.

As early as Pakistan’s first support to the Taliban in 1994, the latter’s potential contribution to the security of a projected gas pipeline from Turkmenistan through Afghanistan to Pakistan, which would have evaded the “natural” pipeline route through Iran to the Persian Gulf, reinforced the idea that the Taliban were part of the U.S. strategic plan to encircle and marginalize Iran. U.S. statements of interest in the pipeline project and speculating that the Taliban takeover of Kabul might bring stability to Afghanistan reinforced this suspicion.

The high point of hostility between the Taliban and Iran took place in August 1998, when the Taliban captured most of northern Afghanistan with massive Pakistani assistance. They had already overthrown Ismail Khan and taken him prisoner. They then captured Kunduz and Mazar-i Sharif. This offensive cut off Iran’s corridor through northern Afghanistan to Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. During the capture of Mazar-i Sharif, Pakistani fighters belonging to the Sunni sectarian organization Sipah-i Sahaba, who participated in the Taliban offensive, massacred eleven Iranians in Mazar, including nine consular officials and a journalist. The Taliban also captured over 100 Iranians assisting the Rabbani government.

These events led to a military mobilization on the Iranian side, and war appeared imminent. There was widespread support in Iran for war against the Taliban. U.N. Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Afghanistan Lakhdar Brahimi intervened to prevent the war. He met with Mullah Omar in Kandahar and President Mohammad Khatami in Tehran and arranged the return of prisoners to Iran. Brahimi attributes his success to Mullah Omar’s interpreter, whom he later learned had toned down both his statements and Mullah Omar’s replies to prevent the meeting from blowing up. In Tehran, Brahimi tried without much success to convince Iranian officials that the Taliban were not a U.S. proxy, but the offer of the return of prisoners managed to deescalate the crisis.

The start of U.S.-Iranian détente during the reformist presidency of Khatami (elected 1997 and 2001) facilitated a reorientation of Iran’s policy in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, though from the Iranian point of view it was the United States, rather than Iran, that changed. The U.S. decision to respond to 9/11 by trying to destroy al-Qaeda and overthrowing the Taliban government appeared to Iran as if the United States had come to its senses and realized where the real terrorist threat came from. In effect, the United States moved from its historic alignment with Pakistan and Saudi Arabia to active cooperation with Iran and Russia. The CIA made the initial contacts in Dushanbe where the United States already had de facto cooperation with Iran on the peace process in Tajikistan. The United States made use of the infrastructure already established in Tajikistan by Iran and Russia to provide assistance to anti-Taliban fighters in northern Afghanistan. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Qods Force commander Gen. Qassem Soleimani personally helped the CIA to establish bases in Panjshir and Bagram. U.S. presidential envoy James Dobbins met with Iran’s ambassador to Afghanistan, Ebrahim Taherian, in Charikar, north of Kabul, together with members of the Qods Force whom the United States designated as terrorists in 2014.

Iran also provided essential diplomatic assistance to the United States at the U.N. talks on Afghanistan in Bonn, where Dobbins worked closely with Iran Deputy Foreign Minister for International Organizations Javad Zarif, who later twice became the foreign minister. At Bonn — where I was senior advisor to Brahimi — Dobbins and Zarif jointly demarched me at breakfast one morning to ask why the United Nations had not included guarantees of elections and counter-terrorist cooperation in the draft agreement. The final agreement included both. Zarif’s private intervention with Yunus Qanooni, head of the United Front (“Northern Alliance”) delegation, resolved the final stalemate over the composition of the interim government.

The Khatami administration expected continued relaxation of tension with the United States, but on Jan. 22, 2002, The New York Times ran an article reporting with alarm that Iran “was working to consolidate its influence in Herat,” a finding similar to an Iranian reporting that the United States was consolidating its influence in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. Within a week after that article, in his 2002 State of the Union message, President George W. Bush labeled Iran as part of an “Axis of Evil” along with Iraq and North Korea. During the Bonn talks, representatives of Donald Rumsfeld’s Defense Department had tried to block Dobbins’ cooperation with Zarif, but the support of Secretary of State Colin Powell enabled Dobbins to continue. Back in Washington, however, the Rumsfeld-Vice President Dick Cheney-led advocates of regime change — first in Iraq and then Iran — won the battle for the president’s teleprompter.

The speech sent shock waves through Tehran that still reverberate today. Equating Iran to Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, which had fought a bloody war of aggression against Iran with U.S. and Saudi help that cost the country an estimated one million lives deeply insulted Iranians, and not just regime sympathizers. There had been resistance in Tehran, as well as Washington, to cooperation on Afghanistan, and Bush’s speech discredited those who had backed that cooperation. Many of them ultimately lost their positions and were sidelined, or worse. The same individuals, who once again gained leadership of Iran’s Afghanistan policy after the election of President Hassan Rouhani in 2013, still refer to it bitterly. At a meeting in Oslo in 2014, one of them commented to me, “If this doesn’t work out, nothing will happen to you.”

After several years, Iran’s position on the U.S. presence in Afghanistan turned more hostile, though it was still counterbalanced by common opposition to Sunni jihadist terrorism (though with differences on who qualified as a Sunni jihadist terrorist, notably Hamas) and Iran’s need for stability along its 540-mile border with Afghanistan. Then the United States invaded Iraq, from which there was no terrorist threat to the United States, and it showed no sign of withdrawing from Afghanistan, but instead turned it into a NATO mission, stationing forces from the entire Western alliance there. Not only Iran but other states in the region questioned whether U.S. objectives were limited to the common goal of opposing Sunni jihadist terrorism. These suspicions were confirmed on May 23, 2005, when Bush and President Hamid Karzai signed a “Joint Declaration of the United States-Afghanistan Strategic Partnership.” While the declaration stated that it was “not directed against any third country,” it also stated that U.S. military forces would continue to have access to bases in Afghanistan, where they would “continue to have the freedom of action required to conduct appropriate military operations based on consultations and pre-agreed procedures.” The first phrase was a profession of intentions, while the second guaranteed capabilities. Security planners in all countries plan against capabilities, which are concrete and observable, not intentions, which are unverifiable and mutable.

The United States had already rejected Khatami’s 2003 offer of a grand bargain and was pressing toward consolidating regime change in Afghanistan and Iraq. Iran, which seemed to be next on the list, was in the midst of the run-up to a presidential election when the strategic partnership declaration was signed. The victory in August 2005 by Mahmoud Ahmadinejad led to the formalization of a new attitude toward the U.S. presence in Afghanistan, though not yet the Taliban. Ahmadinejad asked Karzai for a strategic partnership declaration with Iran similar to the one he had signed with the United States. U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice squelched that idea. As the situation in Iraq stabilized from catastrophe to disaster, the rumblings for regime change grew louder in Washington. On May 11, 2007, Cheney warned Iran — while standing on the U.S. aircraft carrier John Stennis (named after a staunch white supremacist senator from Mississippi) — that the United States was prepared to use its naval power against Iranian threats. In September 2007, Gen. Mohammad Ali Jafari, the newly appointed commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, announced that henceforward, if the United States attacked Iran, Iran would respond against U.S. forces and assets wherever it could reach them. Iranian officials confirmed that included in Afghanistan.

A few weeks after Cheney’s performance, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, speaking in Kabul with Karzai, told the press that the United States was observing “insurgents in Afghanistan” receiving shipments of arms from Iran, but that he could not say with certainty if the government was involved, given the volume of smuggling across the border. On his way home while in Germany on June 14, no longer constrained by Karzai’s sensitivities, Gates said that the volume of the arms flow was such as to suggest that the Iranian government knew of them. U.S. Under Secretary of State Nicholas Burns made more specific accusations on CNN, that there was “irrefutable evidence” that the arms were being supplied by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. In September, after Gen. Jafari had announced the new policy, Central Command’s Adm. William Fallon told the press in Kabul that Iran was “clearly” supplying insurgents in Afghanistan with parts needed to manufacture the same explosively formed projectiles that had done so much damage to U.S. troops in Iraq.

The perception that both the presence in and withdrawal from Afghanistan by U.S. forces posed threats to Iran continued to shape Iranian views of the Taliban. Previously, Iran had viewed the Taliban as part of network of Saudi-sponsored Sunni jihadist groups targeted against Iran with U.S. backing. It opposed attempts at political outreach to the Taliban and denied that the Taliban differed substantially from al-Qaeda. As Iran became more concerned by the threat that a long-term U.S. military presence in Afghanistan could pose, it gradually developed a two-track policy.

The Taliban had begun a diplomatic offensive in 2007 aimed at convincing the United States and the neighbors of Afghanistan that their goals were confined to Afghanistan. They wanted to convince the United States that they could cease providing refuge to al-Qaeda if the United States withdrew its troops. To Iran and Russia, who had similarly hostile views of the Taliban, they emphasized a common interest in opposing the U.S. military presence in Afghanistan, while assuring them that they harbored no plans against any of Afghanistan’s neighbors. At that time, the Taliban were still on speaking terms with Saudi Arabia, where King Abdullah hosted a reconciliation iftar among Afghans during Ramadan in September 2008. According to one organizer of the meeting, in which some senior government-affiliated Afghans participated, Iranian Foreign Minister Manouchehr Mottaki then asked his Afghan counterpart, Dr. Abdullah, why the Saudis were trying to bring back the Taliban. As long as the Taliban appeared to be close to Saudi Arabia, there was a limit to the relations Iran would have with them.

In 2009, however, Saudi-Taliban relations broke down. When Saudi intelligence chief, Prince Muqrin bin Abdulaziz, met Taliban political envoy Tayyib Agha in Jeddah, the two got into a heated argument over Taliban resistance to Saudi preconditions for acting as a mediator with the U.S. and Afghan governments. King Abdullah insisted that the Taliban publicly denounce al-Qaeda before the Kingdom would act. The Taliban insisted such an action could come only at the end of a process, not before. Muqrin expelled Tayyib Agha from Saudi Arabia. Soon after, Muqrin received a visit in Riyadh from Pakistani intelligence chief, Director-General of Inter-Services Intelligence Lt. Gen. Ahmad Shuja Pasha, who admonished his Saudi brothers for acting without consulting Pakistan. Two things happened after that meeting: Saudi Arabia became irrelevant to the peace process in Afghanistan, and Muqrin and his associates started telling their U.S. counterparts that Tayyib Agha was an Iranian agent being paid $10,000 per month by Soleimani. U.S. intelligence was unable to verify the latter claim.

After that, the Taliban shifted to working with Germany and Qatar as intermediaries, and direct talks with the United States began in Germany on Nov. 29, 2010. Tayyib Agha told his American interlocutors that Iran was Afghanistan’s “most dangerous neighbor.” Iran tried to capitalize on U.S. contacts with the Taliban to sow suspicion between the Afghan government and the United States. In one small example, during 2011, when I was an advisor to the U.S. State Department Special Representative on Afghanistan and Pakistan, a senior Afghan official told me that an Iranian official he met in Turkmenistan had told him that I had met with Mullah Omar in Quetta, Pakistan. I am not sure he completely believed my denial.

The outreach to the United States and others was part of a Taliban strategy to capitalize on their demonstrated military and political staying power by seeking international recognition as a legitimate political movement rather than a terrorist group. As a domestic counterpart of this policy, the Taliban also tried to downplay their Sunni sectarian allegiances. During their rule they had engaged in several massacres of Hazaras, a predominantly Shi’a ethnic group, and Shi’a in Afghanistan still largely regard the Taliban as the sectarian equivalents of ISIL. In their public statements and media releases, however, while the Taliban did not compromise their allegiance to Hanafi jurisprudence, they began to publicize their alleged good relations with some Hazara populations and state that they regarded them as fellow Muslims and “Afghans” (citizens of Afghanistan). This did not persuade many Shi’a in Afghanistan, but it made it easier for Iran to engage with the Taliban and capitalize on their common opposition to the U.S. military presence.

Periodically, intelligence reports surfaced claiming that Iran had started providing not only projectile components but also anti-aircraft weapons to the Taliban. As recently as January 2020, I was shown a video of Soviet-manufactured ground to air missiles that Taliban in Helmand had allegedly obtained from Iran. There is no evidence of the use by the Taliban of such anti-aircraft weapons thus far.

During the Obama administration, as the United States opened negotiations with both Iran and the Taliban, Iran seemed to conclude that it would need to deal with the Taliban as a future component of Afghanistan’s political scene. Throughout this time Iran continued to enjoy warm relations with the Afghan government, aside from long-term interstate disputes over water, migrants, and drug trafficking. Iran also continued to fund and support important opposition leaders who supported the constitutional system.

The combination of leadership struggles and pressure from Pakistan pushed the Taliban leadership closer to Iran after 2014. After the Taliban’s expulsion from Afghanistan by the U.S. 2001 military offensive, Deputy Leader Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar took over reconstitution of the Taliban leadership in Balochistan and Karachi, while Mullah Omar remained out of sight. Baradar’s leadership was undisputed. The arrest of Baradar in a joint CIA-Inter-Services Intelligence operation in Karachi in January 2010 led to a leadership dispute. Akhtar Muhammad Mansour became the first deputy leader, while Abdul Qayyum Zakir became the second deputy leader. Mansour claimed to have the same authorities as Baradar, reporting directly to Mullah Omar and supervising the entire Taliban organization, with Zakir reporting to him as deputy leader for military affairs. Zakir claimed that he and Mansour were peers, both reporting to Mullah Omar, with Zakir responsible for military affairs and Mansour for political and civilian affairs.

Both Mansour and Zakir were from Helmand province, from the Ishaqzai and Alizai Pashtun tribes respectively. Both of these tribes are deeply involved in the production, refining, and trafficking of opium. The town of Zaranj on the Afghan-Iranian border is only 136 miles by road from Delaram, where the sole bridge across the Helmand river is the major transit point for heroin from Helmand headed for Iran. At Delaram (where I stopped in a tea house in June 1998, while traveling from Kandahar to Farah as a U.N. consultant) the road to Zaranj and the Iranian border branches southwest from the Kandahar-Herat segment of the Afghan ring road. That route traverses Nimruz, the only Baloch-majority province of Afghanistan, which borders the Pakistani province of Balochistan and the Iranian province of Sistan-Baluchistan. The Baloch, who live in the region where the three countries meet, easily cross the borders, dominating the region’s licit and illicit cross-border trade.

While the Baloch in Afghanistan have no quarrel with a weak state that largely leaves them alone, their co-ethnics in Pakistan and Iran have each struggled for independence or autonomy. In Pakistan, the Baloch National Front espouses a secular nationalism, and over decades past benefited from support from India, the Soviet Union, Iraq, and Afghanistan. Iranian organizations such as Jundullah have adopted Sunni or even Salafi Islamism and received aid from Saudi Arabia operating through Pakistani territory. Both Pakistan and Iran believed (with some factual basis) that their respective Baloch movements receive support from their inveterate enemies, India for Pakistan and, in addition to Saudi Arabia, the United States for Iran. Israeli agents pretending to be Americans provided covert aid to Jundullah in 2007 and 2008 until the United States found out and asked them to stop.

The narcotics threat became intertwined with Iran’s concerns over Baloch separatism and Salafi terrorism. In early 2009, before I joined the Obama administration, an Iranian official told me that the counter-narcotics directorate in the Iranian Ministry of Foreign Affairs was increasingly concerned over links of Jundullah not only to the drug trade, but also to Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the United States. A similar message came through other channels, which along with terrorist acts by Jundullah that killed civilians, led the Obama administration to designate Jundullah as a foreign terrorist organization in November 2010, though not without lengthy internal resistance and delays, which rendered the designation almost useless as a confidence-building measure.

Starting around 2014, the rise of the ISIL, plus the establishment of ISIL’s Khorasan province in Afghanistan, confronted Iran with a new threat on both its western and eastern borders. ISIL controlled an area of Jawzjan province in northwest Afghanistan, on the border with Turkmenistan (which Russia considered a direct threat) and astride the road linking Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Mazar-i Sharif to Mashhad, the capital of Iran’s Razavi Khorasan province. The Afghan monarchy had settled Ishaqzais and Alizais from Helmand in Jawzjan for support in dealing with the largely Uzbek population, and these tribes maintained their family and clan links to Helmand. Ishaqzais and Alizais expelled from Jawzjan by the U.S.-supported forces of Uzbek, formerly Soviet-aligned militia leader Abdul Rashid Dostum in 2001 took refuge with their fellow tribes in Helmand. There they learned the skills of opium poppy cultivation, which some of them eventually took back to Jawzjan.

The changing dynamics among Pakistan, the Taliban leadership, and the United States presented Iran with new opportunities for dealing with the interlinked problems of drugs, terrorism, external subversion, and separatism in the Iranian-Pakistani-Afghan Baloch zone. With the apparent authorization of Mullah Omar, Mansour had taken over the supervision of Tayyib Agha’s outreach from Mullah Baradar after the latter’s detention. He did not, however inform Mullah Zakir, or Mullah Hasan Akhund, the chair of the leadership shura. When the news leaked in 2011, this intensified the dispute with Zakir, which culminated in the April 2014 dismissal of Zakir as deputy leader and head of the military commission.

Subsequently, both Zakir and Mansour were reported to have spent time in Iran as guests of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. Zakir seems to have been looking for a base from which he could operate with more independence. He also began spending more time in Helmand rather than Pakistan. In 2015, Mansour came under increased pressure from Pakistan to participate in Pakistan-based talks with Afghanistan’s High Peace Council. When under pressure, he authorized some Taliban individuals with particularly close relations to Pakistani intelligence to participate in a meeting in Murree in July, the demand by others in the leadership to know whether Mullah Omar had authorized this deviation from longstanding policy led to the revelation that the leader had died two years earlier.

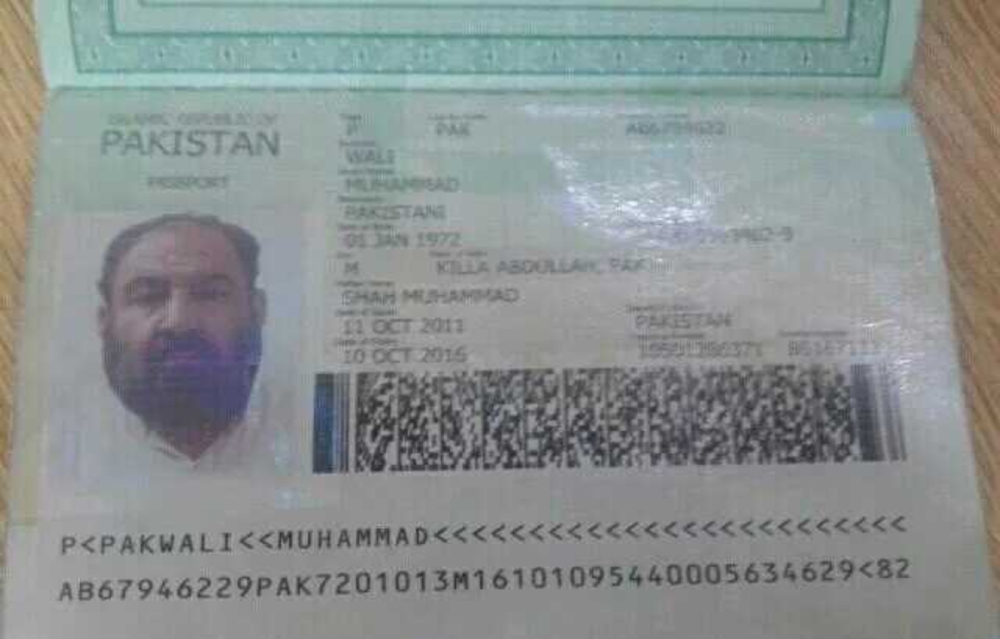

Mansour, who had already been acting as Mullah Omar’s successor, managed to make it official, but only after a leadership struggle that took several months and involved overcoming resistance from Mullah Omar’s family. Pakistan exploited the rift to get its favorite, Sirajuddin Haqqani, son of the late commander Mawlawi Jalaluddin Haqqani, appointed as deputy leader in charge of military affairs. One of the means Mansour used to resist the increasing pressure was by reaching out to Iran, where he stayed for weeks at a time in February, March, and April to May 2016. On May 21, he was killed by a U.S. military drone launched from Afghanistan, while driving across Balochistan from the Iranian border to his home in Kuchlak, a town just outside of Quetta. Someone posted an image of his pseudonymous passport on the Internet, which was in a surprisingly pristine condition considering that it was supposedly salvaged from a taxi of which only charred embers remained (see photograph). This has led to speculation that the passport was actually photographed at the border crossing by Pakistani officials who alerted the United States to Mansour’s whereabouts.

Figure 1: Photograph of Akhtar Muhammad Mansour’s Passport Allegedly Retrieved from the Wreckage of Drone Strike

Source: Voice of America

I have no direct knowledge of what Mansour discussed with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps for several months, but it does not appear to have been a courtesy call. Since then, Iran has established open political relations with the Taliban. It has invited delegations, including one led by the deputy leader and head of the political office, Mullah Ghani Baradar, whom Pakistan released from eight years of detention in 2018 at the request of the United States to lead the negotiating team in Doha.

According to a variety of reports, the talks dealt with the linkages among all the topics discussed above: the common struggle against the U.S. presence in Afghanistan, managing the heroin trade from Helmand in such a way as to keep its profits out of the hands of Saudi-supported Baloch groups, securing the Iranian-Afghan border from groups such as Jundullah, cooperation in the fight against the self-proclaimed Islamic State, and intelligence cooperation regarding U.S. military and intelligence operations in Helmand and along the border. Those visits were managed by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps without the participation of the ministry of foreign affairs, which may have learned about them at the same time as the rest of us, when Mansour was killed, but since then the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has opened political talks with the Taliban, including at least one meeting in Tehran between Iran foreign minister Javad Zarif and Mullah Baradar.

Iranian officials have since that time informed the Afghan government of their relations with the Taliban. In December 2018, Ali Shamkhani, secretary of Iran’s Supreme Council for National Defense, visited Kabul to brief the Afghan government. Iran told the government that it was supplying the Taliban with light weapons in order to deal with security concerns on the Afghan side of the border, but that it did not supply weapons capable of changing the political situation in the Taliban’s favor — in other words, no man-portable air-defense systems. The concerns include all the topics mentioned above, though it is unclear what agreement they reached about narcotics trafficking. Iran’s relations with Taliban on the border seem to be mainly channeled through commanders belonging to Mansour’s Ishaqzai tribe, who are deeply involved in the drug trade. There are reports that elements of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps are complicit in the trade, and perhaps one should not credit even the piety of the defenders of the Islamic Republic with the capacity to make that country the only one between Karachi and Moscow where the security forces have not been corrupted by contraband billions. More fundamentally, though Iran, like the United States, claims to be totally opposed to the drug trade and touts its efforts against it, in neither case has counter-narcotics policy prevented intelligence and military cooperation with traffickers when deemed necessary for national security.

Shamkhani addressed one particular incident that had strained Iranian-Afghan official relations. In May 2018, the Taliban mounted an attack on and nearly captured the city of Farah, center of the province of the same name on the Iranian border with a population of about 500,000. Afghan officials charged Iran with “directly funding and equipping the Taliban in Farah.” The head of the Afghan border police in the province said that “Revolutionary Guard commanders are leading the firefight” there. During a visit to Kabul in January 2019, I was told by Afghan officials that Shamkhani did not deny the Iranian role, but rather expressed Iran’s serious concern about what he claimed was a significant presence in Farah of U.S. intelligence agencies carrying out surveillance and operations in Iran. That, he implied, was the target. The Afghan government just happened to be in the way.

This lugubrious morass of countervailing intrigues provided the context for Tehran’s statements, carefully straddling the invisible line between nuance and incoherence, on the U.S.-Taliban negotiations in Doha. With channels to all camps, and the direct threat to Iran from the United States largely neutralized for now, Tehran has retained freedom of action to confront whatever further vicissitudes may agitate its relations with its eastern neighbor.

Barnett R. Rubin is director of the Afghanistan Regional Program, Center on International Cooperation, New York University, and former senior advisor to the U.N. special representative of the secretary-general for Afghanistan and the U.S. special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Image: Department of Defense (Photo by Resolute Support Media)